The Frostling

It was on a bus ride to school one early March Friday morning that Jelena for the first time clearly saw a frostling crouching atop a car and with a knot of anxiety tightening in her gut silently accepted her father’s legacy had arrived almost in full.

“U krasni kurac,” she cursed under her breath as she looked away and back again. But the frostling was still riding the old Renault Four directly behind the bus, just one of the many vehicles winding their way from Grobnik to Rijeka. She’d seen drawings in the Book of the Bells which Old Robert would show her during their training sessions, but the real thing was something else: lines in pencil or ink on paper could never capture the sheer alienness of the creature. Skin vibrantly green or blue, depending on how light caught it, veined with dark streaks and dusted with sparkling frost. Limbs short and stick thin, the narrow body bent as the frostling hunched, looking at the world around him out of deep set eyes, perfectly round and snow white, pupiless. It was no bigger than Lola, Tara’s husky, but where that dog was pure friendliness, to Jelena’s eyes the frostling radiated cold indifference.

Shifting a little in her seat at the very back of the old, rickety bus and earning a grumpy glance from the woman next to her, Jelena followed the creature’s gaze.

Fog was thick in the Rječina canyon, but sun had found a crack in the overcast sky, beams outlining gray skyscrapers and making the calm Kvarner glitter.

On any other morning, Jelena would have enjoyed the view and ignored anything that only she could see.

For weeks she’d been seeing blurs, vague outlines, and blobs: moving across meadows, crawling up walls, sitting on rooftops, slinking along tree branches, scurrying down the middle of the street. Unobserved, undetected by any eyes other than hers.

For months prior to that she’d been aware of something, a general notion of presences around her, some static and others in motion, until one day it wasn’t just a vague sense any more, but an actual hazy outline of a… thing moving on the other side of the village road as she walked back home.

It was all natural, Old Robert had told her back when the training had started. First comes the awareness, then the blurs, and then, one day, she’d be seeing the spirits in full detail.

She didn’t like the full detail. It was more disturbing than just dark, amorphous outlines in the background of her everyday life—and literally impossible to ignore. In fact, she realised she was staring at the frostling, her mouth slightly agape, taking in its appearance, as real as the car it rode on, as real as the woman next to Jelena, as real as the press of bodies on the bus and the murmur of teenagers going to school and grown ups on their way to work. Dozens of people, completely unaware of the frostling, their world, in essence, the same as it had been the day they were born.

She took out her phone and realized a crowded bus was really not the place to have certain kinds of conversations. She also noticed Tara hadn’t replied to her text. Maybe she’d overslept, and was now riding the later bus, cutting it close but still making it just in time. Jelena hoped that was the case; Tara really couldn’t afford any more missed classes this school year. Jelena too, to be fair.

As the bus took a right turn at Orehovica and continued its slow descent towards Rijeka, Jelena found herself glancing over her shoulder and out of the rear window, first at the frostling, and then, for just a moment, at something long and tall and spindly and dark red bounding from treetop to treetop deep down in the Rječina river canyon.

The Grey Steel Door

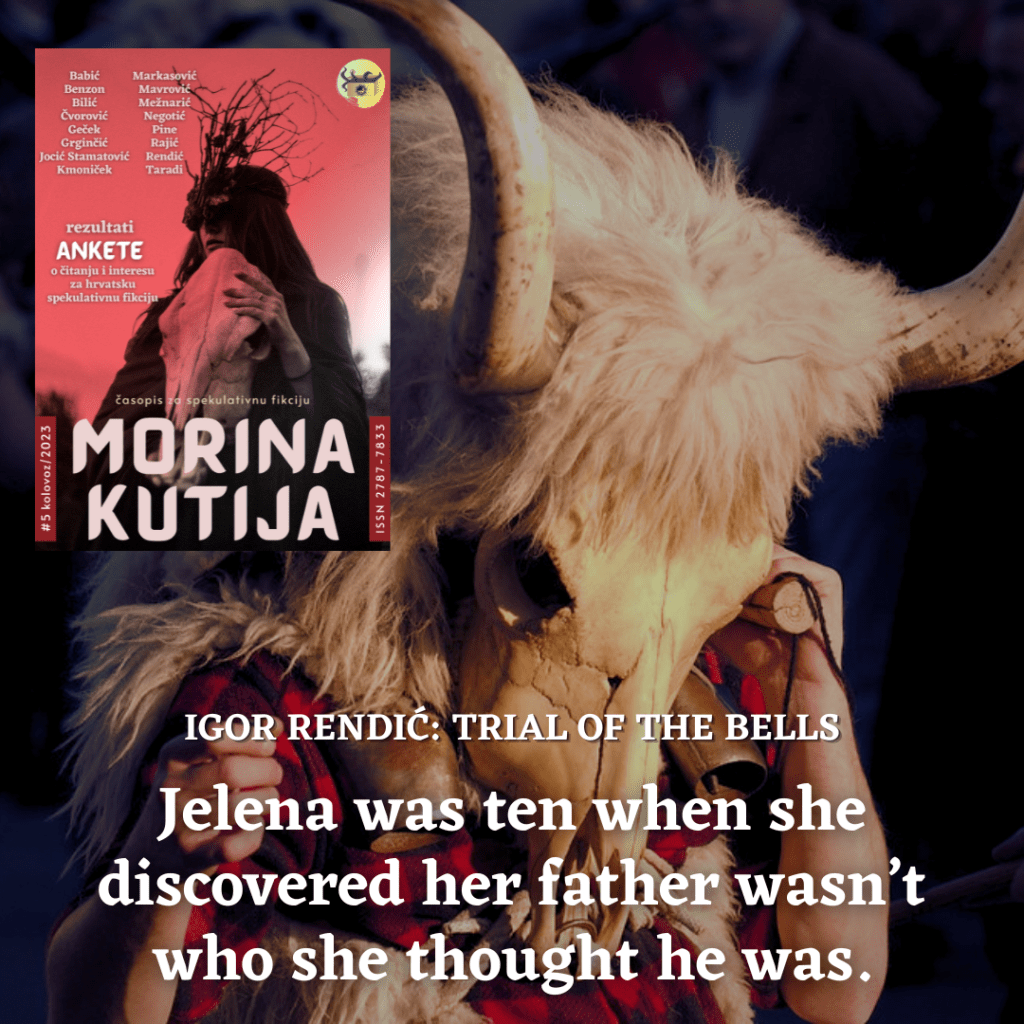

Jelena was ten when she discovered her father wasn’t who she thought he was.

Their house was one of the few old ones still standing in the village, stone walls and a wooden roof instead of brick and concrete; it had a big front yard and an even bigger back one, opening onto a large meadow. Several outbuildings were dotted around the house: an old wooden shed, a newer concrete one, a seemingly ancient and decrepit wooden goat house. All amazing places to play when you’re a kid, all places she would know every inch of by heart long after she stopped playing there.

There was always just one place she couldn’t go.

The basement had two doors. One was inside the house, in a small room next to the kitchen; a creaky wooden door with concrete steps on its other side, leading down into the dry dark. The other was outside, at the back of the house, a slab of dark gray steel with a padlock on it.

The basement was chock full of boxes and crates and, at a first glance, it was just a single space. As a child, Jelena liked to go down there, despite her fear of dimly lit spaces—or because of that fear. A part of her genuinely enjoyed the buzz of anticipation and creepiness even as her ears listened for the faint sounds of monsters lurking from behind their cover, stalking her as she explored. But there were no monsters back then, no creatures of any kind in the dark basement except the occasional spider.

It took her several visits to the basement—always waiting for Mom and Dad to be out of the house, preferably at work or visiting neighbours—to realise there was no steel door on the inside. This led her to discover one of the concrete walls was lighter in colour than others, which she guessed meant it was a new one.

She asked her parents why they didn’t remove the steel door if they weren’t using it anymore.

Mom and Dad exchanged glances and then, after a moment, Dad smiled and said, “That’s because we didn’t seal the door. There’s a room on the other side,” he continued, Jelena’s attention now fully on him, the movie they were watching from the couch completely forgotten.

“It’s locked for a reason,” Mom put in quickly.

“Yes,” Dad said. “There’s an old gas heater in there. You know the one your grandpa has to heat up the water in his bathroom?”

Jelena did. She was always a little wary of it. TV taught her that gas explodes and Grandpa’s heater was always making weird noises so she would always wonder if it would explode while she was visiting him.

“So, there’s a big one down there,” Dad said and then quickly added, “but don’t worry, it won’t explode. It’s just that it’s very big and very heavy and we couldn’t move it without taking it apart, and it’s so rusty that it would make a horrible mess and take a really long time.”

“But why did you build a wall around it?”

Mom smiled. “Because we didn’t want you to hurt yourself while you’re playing down there.” Her right eyebrow crept up just a little. “We know.”

Jelena’s mouth just made a silent oh.

“So, that’s why there’s a padlock on the door,” Dad said.

Jelena just nodded, the allure of a sealed, secret room fading away to nothingness. She nestled back between her parents, turned her attention back to the screen.

Three months later, on a gray, drizzly afternoon, as she was returning from playing in the goat house with Tara, passing by the steel door, she noticed the padlock was hanging open.

She did a double take, stopping mid-stride. She glanced over her shoulder, but Tara was too far away to hear her if she called out, running across the meadow back towards her house.

Holding her breath in excitement, Jelena pushed open the door. There was no creak, just a barely audible whoosh as the slab of steel revealed… a dark space.

It took her a long moment to put her right foot on the first concrete step, but once she did, the rest were no problem at all and before she knew it, she was at the bottom. She glanced over her shoulder, just to make sure the steel door wasn’t closing on its own.

The dark turned into a gloom as her eyes adapted while she descended. It was… just a room. Small one, with a metal bench set into a wall to her left.

Absolute disappointment.

But… where was the giant water heater? She turned to the left, peered into the gloom.

She didn’t scream only because her throat had seized up.

Someone was there. Someone big, so big, a giant—

It wasn’t a giant.

It was a monster, skull with horns and no skin, huge empty eye sockets staring straight at her and any moment there would be a mouth and teeth and—

She stumbled backwards, wanting to cry out for Mom and Dad.

It… wasn’t a monster. It wasn’t alive.

Her eyes could make out details now. The thick fleece under the skull, a strong smell of something old filling her nostrils. A long stretch of dark fabric hanging beneath that. To the left of it, danlingfrom a hook (the skull must have been on a hook too, it wasn’t anyone standing there, it was just a skull and fleece and a—a shirt?—on a hook), something long and wooden and metal, and to the right of the skull, on yet another hook, chains with something…

Bells. Large cowbells, bigger than her head.

Standing in total silence, not daring to take a breath because—because something might happen—what might happen?—Anything.—Jelena took a step forward.

Was she afraid? Absolutely. But she was also curious and her curiosity was stronger, by the tiniest amount, but it was enough.

It was just a skull. And just a fleece. And just a stick. And just some bells.

She reached out.

The fleece was coarse, but warm under her fingers. Invitingly warm in the cold and dry basement.

The skull was smooth, her fingertips gliding over the curve of its bottom—she couldn’t reach up, touch the hole where the nose would be, let alone the horns, and it—

Wind. The hum of a breeze building into a roaring gale.

The potent animal smell of fleece.

The heft of wood in her hand, reassuringly heavy, inviting her to swing and strike.

Footsteps. Hissing. Clicking. Growling. Chittering.

Movements. Sliding across wet stone. Hooves on rock. Talons on tree bark.

In front of her: a river, winding through a forest, trees bent, thick with leaves, branches reaching to one another, forming an arch over a path, bare soil stretching through knee-high grass.

Above her: through the branches and the canopy, the dark vaulted expanse of a cave’s ceiling, dotted with crystals glittering like stars.

And rolling in like thunder, rising from all directions: the clangor of bells, drowning out the world.

The back of her legs hit against the bench and finally she let out a sound, a startled yelp.

There was someone in here with her.

A hand touched her arm.

“Hey, hey, it’s okay, honey, it’s alright.” She held onto Dad hard, suddenly afraid that the skull might sprout hands and grab her.

He reached to the side and light flooded the tiny room.

“It’s okay,” Dad said, smiling down at her teary eyes. He peeled her off himself gently, turned her, hands on her shoulders, firm and reassuring. “Look. It’s just a costume.”

And it did look like just a costume. Just like the ones she’d seen so many times before. Only it wasn’t anything like that and this she understood somewhere deep down. She couldn’t explain how, but it was a dead certainty in her young mind, as immutable as Dad and Mom being in love, the sun rising in the east, and Tara, if given even half a chance, eating so much chocolate that she’d feel sick afterwards.

It wasn’t a bellringer’s costume. Jelena had no idea what it was, but it absolutely wasn’t that.

“It’s not,” she whispered, unable to take her eyes off it, now bathed in yellow light.

Dad took her by the hand and sat them both down on the small bench. She leaned into him, holding onto his arm, pressing her cheek into the soft fabric of his woollen shirt.

“You touched it? It’s okay, you didn’t do anything wrong.”

“I did,” she said, watching the costume, waiting for it to move under the harsh light of the bare bulb.

“You heard things?” He was looking down at her, smiling kindly. Looking up, she gave the faintest of nods.

“And you smelled something?”

Another nod.

“And you saw something? For a moment or two it was like you were in some other place?”

Her eyes as wide as they could be, she said, barely louder than a mouse: “Yes.”

Dad closed his eyes and a look of sadness crossed his face, but it was only a tiny cloud, chased away immediately by the sun of his loving smile. He stood up.

“I’m not going anywhere,” he said in response to her clutching his arm tighter. He removed the mace from the hook, sat back next to Jelena. He placed the carved wood in her hands. It was so heavy that she couldn’t hold it, and had to rest it on her knees. The wood was grainy under her fingertips, a worn leather strap wound tight around one end, a length of that same leather forming a loop to hang the mace from; strips of dark, polished metal set into its other end. Jelena felt the thing was bigger than her, bigger than this room, bigger than their house.

Dad took her by one hand again and suddenly a connection came into being. One hand on the mace, the other in her father’s palm, Jelena felt… felt like she’d been asleep so long, her entire life maybe… but now waking…

… her father’s eyes, so kind, so loving, so… sad, his gaze locked with hers… don’t cry, Dad, she wanted to say… it’s alright…

He was kneeling in front of her now, sad, yes, so sad, but also proud.

“I want you to know,” he said, voice heavy with emotion, “that you don’t have to do anything you don’t want to. Do you understand, honey? No matter what people tell you, if you don’t want to do something—if you really, truly don’t want it, you don’t have to.”

Jelena didn’t know what to say. Was something wrong? She’s done something wrong, hasn’t she? He said she hasn’t, but she has, hasn’t she, and now it was all going to go bad in some way, some horrible way—

Her father swallowed, smiled and took the mace from her, set it down on the stone floor. Then he clasped both her hands between his palms.

“I’m a bellringer,” he said.

Jelena’s eyes strayed to the costume on the wall for a moment. Yes, it looked like the ones she’d see every year during the carnival season. No, it wasn’t that.

“But… a real one,” he continued, and then gave the faintest chuckle. “I know, honey. What you heard and smelled and saw, that was real. You had a… a vision.”

“Like… in the movies?” she asked timidly.

“Something like it, yes.”

“It was… magic?” she breathed the word out, afraid of… what, exactly?

“Yes.” He’d said it so simply, as if she’d asked him if Lola was a puppy. “Yes,” he repeated. “I’m a bellringer.” Then he gave her hands the gentlest of squeezes. “And so are you.”

Tailbone

Open the window, the text message said. Jelena sighed as she stood up, walking down the length of the class, between students chatting lively, copying homework, showing off new shoes or skirts. The window in question was at the back of the class, looking onto a side street. It was also about two metres from the ground, but that never stopped Tara.

As Jelena was opening the window, drawing a curious look or two from nearby students since the morning air outside was still cold, a rickety red Golf Three slowed down at the far end of the street and someone literally jumped out of the passenger side door, running full dash towards the school.

It was Tara alright, once again hitching a ride with her neighbour’s son. The car drove on, the young man behind the wheel on his way to his shift at the 3. maj shipyard.

For a moment Jelena thought she was seeing things, that some spirit or creature had attached itself to her friend’s head, but no, Tara’s hair was emerald green. So that was what she’d meant yesterday when she’d texted there’s something she can’t wait for Jelena to see tomorrow.

Oh, the headmistress was going to love it. Then again, Tara, with a less than stellar attendance record, also aced pretty much every exam (when she could be bothered to actually study for it; her grades were an unholy mess) and had twice now won first place in national history and chemistry competitions, providing their school the opportunity to keep lording it over other high-rankers, so—in Tara’s words, but only for Jelena’s ears—the headmistress could suck it.

This was all to say that Tara was constantly dancing on a razor-thin line, her academic successes pretty much the only thing allowing her to maintain her… unique fashion style. She was a little punk, a little goth, a little metal—and all that in a high school that didn’t really approve of any one of those on their own, and that didn’t actually have student uniforms, but would have really, really liked to introduce them.

Overall, Jelena firmly believed that the headmistress was going tobreathe a sigh of relief when, in just a few short months, Tara graduated and left to become some other authority figure’s problem.

Tara didn’t stop nor really slow down as she reached the wall directly under the window. Rather, she hopped, found purchase with a foot and a hand and stretched her other hand up, reaching.

Jelena was there to reach down as far as she could, bending over the windowsill, and grab the outstretched hand.

Then she began pulling up as Tara’s Doc Martens scrambled up the wall.

“How—are you—so heavy,” Jelena grunted, dragging her friend up. A year ago this would have been an impossible task and not because Tara was stout, as she liked to call herself. A year ago Jelena was—well, willowy was the way her mother put it. But puberty and her training sessions changed that and while she stayed lean, she was also a head and a half taller now and had her gym teacher regularly ask if she’d be interested in trying out for the school’s volleyball team. Looking in the mirror, Jelena couldn’t see that much actual difference in the size and shape of her body between then and now—she was more focused on her hair, which had started turning from light brown to light red in the past six months. But she did feel—no, was dead certain—that she could have carried that younger Jelena in her teeth and not break a sweat, to borrow Old Robert’s phrase.

“Hey, screw you,” Tara snapped. A beam of sunlight broke through the clouds, bathed the street and made Tara’s floppy emerald spikes practically glow.

“I didn’t say fat-I-said-heavy,” Jelena said through clenched teeth as Tara grabbed onto the windowsill. A moment later she was kneeling on it and then, instead of sitting down, Tara decided to stand up, smiling triumphantly at several girls and boys who’d been watching the show and were now nodding appreciatively.

Then the classroom door opened and Tara would have jumped down into the classroom, only she slipped and ended up dropping on the windowsill.

Jelena winced once and then again when she noticed Tara’s shoulders clenching and her friend biting her lip, eyes squeezed shut.

“You okay?” Jelena whispered in concern as the Greek professor entered, not really paying attention to the students taking their places.

“Tailbone,” Tara whispered. She stood up gingerly. “It’s not broken,” she breathed out, walking down to her and Jelena’s bench.

Tara winced when she sat down, but only slightly, then took a deep breath and turned to Tara as the professor began taking attendance. “You like it?” she asked, shaking her head a little, making the spikes flounce gently.

“It’s very green,” Jelena said, smiling appreciatively.

Tara gave a smug grin. “I’ve got a blue dye as well, I think it would look good on you—”

They were interrupted by a very loud clearing of the throat. The professor gave them a pointed look, then gave Tara and her hair another one, then sighed, obviously deciding it wasn’t his problem to deal with.

“What’s wrong?” Tara whispered as the lecture started, the professor droning on and on about the great heights the Hellenic culture had reached long, long ago. She was looking at Jelena, concerned. She’d always been great at detecting if something was bothering her friend.

“I’m… seeing things,” Jelena whispered back, head low as if that would make the words even harder to hear by unwanted ears.

“Don’t you already—ooooh.” Tara’s mouth hung open for a long moment, then clamped shut. “Shit.”

“Yeah.”

“You okay?”

Jelena gave a sour smile. She glanced at the professor, but he had his back to the class, writing out a long quote by Herodotus, sounding out each word. “It’s freaky. Nothing is blurry any more and some of the things are… Freaky.”

Tara glanced around, leaned in a little more. “Are there any in here with us?”

“No. But there was a big dark yellow one on one of the roofs to the left of the school. Like—like a huge snake, only covered in wriggling fungus. Nasty.”

“Fungus.”

“Yeah.”

Tara winced. “That is nasty.”

The Flying Pizza Dough

Jelena was also ten when she discovered her mother wasn’t who she thought either.

It happened a few minutes after her father had told her who and what he really was. They locked the gray steel door and walked into the house, Dad talking about letting her have the entire box of ice cream for herself that night, if she wanted.

Mom was in the kitchen, not so much stretching as wrestling with pizza dough, and she turned around when she heard them. “Perfect, I need someone to run to the store, I thought I’d bought olives the other day, but I—” She must have seen it on their faces, some change that Jelena wasn’t aware of but that had written the truth in large letters right across their features. “—didn’t,” her mother finished, setting the dough down absently.

“I found her in the basement,” Dad said. “In the back.”

Her mother’s eyes went wide, her hand reaching for her mouth.

“You won the bet,” he told her then and Mom just let out a barely audible breath, closed the distance and hugged Jelena, getting down on one knee.

“How do you feel, honey?” she asked with care in her voice, gently pushing a lock of hair behind her ear.

“It was scary,” Jelena said. “But I’m not scared anymore.” And she wasn’t lying. All that Dad had told her had removed any fear she might have felt. It was still all strange and new to her and there was trepidation, but she felt—felt like when they would go someplace new. Expectation, maybe a little concern, but no actual fear.

“Dad told you everything?” Mom asked her, glancing up at her husband for a moment.

“Everything she needs to know now,” Dad replied. Then, with a curious smile, he added: “And I think you should tell her something too.”

To which Mom just gave a little sigh, smiled at Jelena, and pulled out a chair, motioning for her daughter to sit.

Then, as Jelena was sitting and watching, her mind still abuzz with what Dad had told her, her mother reached out a hand and flicked her fingers upwards.

And the pizza dough, momentarily forgotten on the kitchen counter, started levitating. It floated up, up, all the way to the row of cabinets above the counter. Mom started moving her entire arm gently and the dough followed suit, flying slowly as if swimming through the air. After which it plopped down on the table next to Jelena, who stared at it for a long moment before she tore her eyes off it and focused on her mother, who sat down on a chair in front of her daughter.

“I’m a—” Mom stopped herself, shook her head with a chuckle. “I was once a witch.”

Jelena’s jaw was on the floor.

The Book of the Bells

During lunch break, she found a secluded spot—the toilet on the top floor of the school—and dialled Old Robert’s number. She ignored the long, eel like shadows coiling in the corner of the room.

“Jelena,” he answered, voice a little hoarse, as always.

“I’m seeing clearly now,” she said, paranoid that someone might walk in, avoiding any details not fit for ordinary people’s ears.

Old Robert just said: “I’ll tell the others.”

“When—when will I…?”

There was a brief moment of silence as she listened to him leaf through some papers on the other side. That ancient notebook of his, cracked brown leather and yellowed paper and thin, spidery cursive.

“Saturday,” came his voice again.

“… that’s tomorrow.”

“Yes.” Then, with calm conviction he said: “You are as ready as you can be.” Then he added: “Come to me first thing after school.”

She had one more call to make. Her mother picked up on the second ring. “Jelena?” she asked, worry in her voice because she didn’t have a habit of calling during school.

“Mom,” Jelena said, voice a little heavy with emotion. “It… it happened.”

***

As she entered Old Robert’s living room that afternoon, coming there straight after school, she stopped short in the doorway.

Standing there, frozen in place, under their collective gaze, she couldn’t not remember the last time she’d seen all these people in the same place. The location had been different, but the people were the same. A little older, but still the same faces: some smiling, others impassive, and the rest… not openly hostile, no, but definitely not thrilled to see Jelena. Just like that day, four years ago.

***

The day of her father’s funeral.

It had been sunny, and that, in Jelena’s mind, somehow made it even worse, though, for her, the day was already the most horrible it could be. Her heart, her entire body so heavy with sadness, she wanted the world to cry for Dad at least a little, for someone else to take the burden of grief that seemed to have fallen squarely and solely on Mom and her.

As far as the world was concerned, Jelena’s father’s heart had stopped beating in his sleep, in his bed and next to his loving wife.

Jelena was to learn the truth in two stages. The first was revealed to her that very same day, by her mother. Her father died doing his duty as a bellringer, protecting people, and the heart attack was just a lie for everyone who didn’t know who and what he really was. Jelena asked what it meant exactly, and was told Mom would tell her one day. It wasn’t fair, but when she wanted to rage and cry about it, she saw Mom’s grief—stricken face and pushed all that aside. She could wait. It wasn’t important, really. Dad was gone.

His funeral was well attended because Dad was well loved by neighbours, had many friends and acquaintances who wanted to say their goodbyes to a good and kind man who was always ready with a helping hand and good advice.

She knew Old Robert even back then, but only as that old man who’d sometimes visit Dad, bringing a bottle of rakija for him and Mom. He’d stay, talk with Dad in the living room while Mom would take Jelena to help her cook or teach her how to mend her clothes or just go play with her in Jelena’s room.

The day of the funeral Old Robert was there, as were the nine men and women who stood close to him, a group within a larger group. Jelena noticed that, as she tried not to look at the casket. They were all of different ages, and while they all wore black, there was nothing to hint that they shared a single, strong bond. And yet, Jelena could feel it in the air: something invisible and intangible that bound them together, making them stand apart to her eyes even as they melded into the crowd of mourners.

And as she watched them, she noticed they were in turn observing her. Not the casket, and not Mom, who was doing her best not to break down sobbing and who Jelena had been emulating that entire day. No, they were watching Jelena.

Some, like Old Robert, had sorrow in their eyes if not on their faces. Others, like the local postman Brane, cried openly, wiping red eyes, pushing his unruly dark hair from his face. And then there was a dark blonde woman, looking at Jelena as if she’d done something really, really bad.

***

“So, we are really going through with this?” The dark blonde woman—Marijana—was now looking at her, hiding her contempt well, but over the past two years of bellringer training Jelena had learned to detect it.

Marijana did not approve of Jelena taking the trial. She’d never approve, but Jelena had months ago accepted Old Robert’s words, used them as a mantra to keep away any doubts the woman’s gaze used to have a habit of instilling in her. There’s nothing she can do about it. And if Jelena passes the—when Jelena passes the trial—Marijana will have to grin and bear it, and that will be a tiny victory she’ll savour.

“Yes,” Old Robert said. A simple fact. No room for argument. If a person was called to become a bellringer, if they wished to take the trial, there was nothing that could be done about it. The tradition was ancient and it served the world well.

At least Jelena had been told it was so. She still knew so little, even though it was so much more than two years ago.

The people in this room, all ten of them, had been her father’s brothers and sisters in arms, as he’d once called them. No matter what they felt or thought about each others’ personal lives, choices, and philosophies, where the ancient calling was concerned, they were as one. “There is no other way to do our duty, to survive the battles we face,” Old Robert would often tell her.

On the coffee table they stood around, there was the book. The Book of the Bells, an old, leatherbound, and handwritten volume containing the history and lore of the bellringers—the true bellringers; these ten people in front of her and the hundreds who came before them. And, tomorrow, perhaps Jelena, too, would become one of them.

No. Not perhaps. She would.

She didn’t belong in this room.

The thought was ridiculous, she knew that. And yet it was hard to shake, especially today.

“Are we certain she’s telling the —” Marijana spoke up again, but Old Robert gave the softest weary sigh and looked at her. She nodded indignantly, and took half a step back. Jakov and Tone did the same; the three of them had been against Jelena joining their ranks from day one. It was easy to think of them as following Marijana’s lead, but the truth was they had all developed the same attitude towards Jelena on their own, and Marijana was simply the most forward of them.

Valter, pockmarked and still bright blonde even though he was the second oldest—which was to say, in his sixties, as opposed to Old Robert who was… Jelena had always guessed at least seventy, but Mom once said that it was possible he was over a hundred, that being a bellringer possibly affected your aging—gave her a tight smile and picked up the book, opening it. He stood in front of Jelena, glanced at the page, and looked her in the eyes. His gaze was firm as he took out a piece of charcoal from his pocket.

“As the chronicler of the bellringers, I hereby note that on this day, Jelena, daughter of Borna, a bellringer, and Laura, his wife, has had her fist clear view of the world of spirits and has thus made her final step on the journey as bellringer apprentice. From this moment on, she awaits the trial of the bells when she will either have her name join all the others of our kind, the next in a line stretching back generations uncounted, or fall and be mourned by her friends and family. Here, witnessed by all bellringers currently living, I ask you, Jelena, daughter of Borna, to sign your name for the second time.”

The first had been two years ago, on the first day of her training. You could sign your own name in the Book of the Bells three times at most: once when you became an apprentice, once when the apprenticeship ended and the only thing to do was face the trial; and the last time when—if—you survived the trial and became a bellringer.

All the other times your name might be written down was by the chronicler’s hand, either marking down a deed of particular note… or your death.

Jelena took the piece of charcoal, thin as her pinkie finger, and as Valter turned the book towards her, with a shaking hand she signed her name next to that first signature. She noted that, as much as it was wobbly, the older one was even wobblier.

A sign of progress, she thought amusedly to herself.

“There’s food and drinks in the kitchen, if anyone wants some,” Old Robert said as the mood suddenly shifted and some people sat down, others went to stand a little to the side talking, and Marijana, Jakov, and Tone simply left, saying a quick goodbye to everyone except Jelena.

Old Robert approached her, patted her on the shoulder in a grandfatherly manner. “They stop being disturbing after a while. The spirits.”

She was glad to hear it.

“I’m scared.” It came out of her like a breath, unplanned but inevitable.

Her teacher just gave a tight smile. “Good. I wouldn’t let you do it if you weren’t.”

“What… what should I do? Today?”

“Anything you want,” Old Robert said. “As long as you’re at the cave tomorrow noon.”

Mom

The day Dad died, their house was full of people. Jelena would have been so annoyed, but she was so stunned by loss and grief that she didn’t even notice them milling about, offering kind words that couldn’t reach her.

The day after that, there had only been a single visit. Jelena had spent the afternoon with Tara, sitting on that rock in the woods and talking and crying on her friend’s shoulder. Hours later, feeling guilty for leaving Mom alone, even though Mom had insisted she go spend some time with Tara, they both came back just in time to see two women leave Jelena’s house. Passing them by in the front yard, she said a “Hello” and received a “So sorry for your loss” and compassionate looks from both of them, but they either didn’t want to offer a hug or something in Jelena’s eyes or face told them that the last thing she wanted was more people she didn’t know embracing her.

She thanked them, and as they left the front yard and walked down the street towards a car parked by the streetlight, Jelena and Tara looked after them.

“Who was that?” Tara asked.

“I have no idea,” Jelena said. One of the women was old and had the kind face of a grandmother. The other was younger, maybe Jelena’s mother’s age.

“I would kill for her hair,” Tara said and Jelena now paid attention. The younger woman did indeed have the most stunning head of hair, dark and long and slightly curly.

In the house, they found Jelena’s mother crying her eyes out, but when Jelena ran up to her, asked what was wrong, all Mom had said was that everything was okay and then asked if the girls were hungry and if Tara wanted to stay for dinner.

***

A year later, on the first anniversary of Dad’s death, Mom had finally told Jelena who that woman was.

“She was with your Dad when he died.”

Jelena was stunned at those words. “You said…”

Mom wiped a tear from her eye. “No, no, honey, he was sleeping next to me.” She took a breath, cleared her throat a little. “There is a—a kind of magic that lets you travel outside of your body when you’re asleep. There’s a world you can enter that way, and your Dad could do it.”

Over the years, Jelena had been getting only bits and pieces of the realm her Mom and Dad had inhabited. She’d ask questions, of course, but mostly the answers were “when you’re a little older”. She was bothered by it, but she also understood them both. Mom had been ‘retired’ and so wanted to leave it all behind. And even though she knew very little about what being a bellringer like Dad meant, she had gathered that it was very secret—that even other people who existed in that world Mom and Dad had been a part of mostly didn’t know about bellringers.

“Mom… what happened to Dad?” Jelena asked, a tightness in her throat.

“He was helping someone,” Mom said, eyes misty. “He could never help himself.” She chuckled sadly. Taking Jelena’s hands in hers, she continued: “Someone was in danger—attacked—and your Dad couldn’t stand to the side and watch. And he was hurt.” A soft, ragged breath. “It wouldn’t have killed him on its own, but he was already weak from—the bellringers had—just a few days before that they were—” She was struggling, trying to keep secrets that probably didn’t belong to her.

“Mom, it’s okay,” Jelena said in a cracking voice. “Why did she come here?”

“They fought together,” Mom said.

“All three?”

Mom blinked for a moment, then shook her head. “No, only Le—only the older woman you saw the other day. They fought together, and because of what had happened to your Dad before that, with the bellringers, he was—he…” Her voice broke and she heaved a sob. “He just died. His body gave out, simply… gave out.” Tears glittering in her eyes, she added: “And that woman was with him until the end, so he didn’t die alone.”

She let go of Jelena’s hands, reaching into a pocket of her jeans. There was the sound of crumpling paper as she produced a single leaf, folded over several times. “He asked her to give me a message.”

Her father’s last words on that little piece of paper. Jelena’s mouth was as dry as her eyes were wet with tears.

She started reading, saw her mother’s name and immediately began skimming. Mom wouldn’t mind, she knew that, but it was private—surely the most private and intimate a thing there could be, someone’s dying words?

Her eyes skipped over sentences, searching for her own name. She found it at the bottom.

Jelena, when the time comes, you don’t have to do it if you don’t want to. It is a noble calling, it’s worth doing, but nobody can force you to take my place. Nobody. You do it if you want to do it, and for no other reason.

I’m sorry I won’t be there to see you live your life to the fullest. Just know that I love you. And keep your Mom safe for me. If I ever see you again, I hope it’s not for a long, long time.

She couldn’t say how long she cried, there, in her mother’s arms and holding that piece of paper so tight, as if it were… well, the last thing her father would ever say to her.

After her mother wiped her eyes gently and after Jelena had returned the letter, she had one question remaining.

“Mom, who was that other woman, then?”

Mom gave a small, sad smile. “She and I used to be very good friends, but when I gave up my previous life, I had to leave many of my friends behind as well.” The smile grew wider. “She still checks on me occasionally, though.” There was something in Mom’s voice that told Jelena not only how much she appreciated it but also that the woman really shouldn’t have been doing it, yet obviously didn’t mind breaking rules.

***

Her mother held her for a long time as they stood in the living room doorway.

“So, tomorrow,” Mom said. No panic, no trepidation in her voice—well, no more than if Jelena were to go on a holiday on her own for the first time. But her eyes, oh her eyes. Fear, absolutely. She’d lost her husband, and tomorrow, if something went wrong—

Jelena pressed a palm against her face, gently. Mom leaned into it.

“I know,” Mom said. “I know it’s going to be fine.”

Jelena hoped she was right.

“Did…” Mom asked then as they walked into the kitchen and sat down at the table, “did they all come? You said you were going to Old Robert’s house and your dad used to say that all the bellringers would come together for big moments.”

“Yes, they were all there,” Jelena said.

“Even…” Mom didn’t finish the sentence. She didn’t like saying Marijana’s name.

Mom didn’t like her. Mom, who always had a kind word for anyone, did not like that woman one bit. Because, while Jelena’s mother had been accustomed to people not liking her because of who or what she was—had been, since she’d given up witchcraft and the world of magic, for the most part, years before meeting Jelena’s father—she had zero tolerance or understanding for people disliking her daughter because of her. And also, because Marijana simply refused to see reason.

No matter how many times Dad had told her—and how many times he told Jakov and Tone, the other two bellringers who always held Marijana’s side—and no matter how many times Old Robert said it and no matter how many times all the other bellringers agreed and no matter how many times Jelena’s Mom didn’t do any witchcraft, didn’t in fact do a damn thing apart from being a loving mother and a great wife and an amazing, kind, gentle human being… Marijana still held firmly to her doubts, suspicions, and plain intolerance.

Once a witch, always a witch. And that was an attitude that Mom and Jelena could accept. It was wrong, but it was… tolerable. But to Marijana and the others, it wasn’t just that. Once a witch, always a witch; yes, but also every witch is a štriga at heart. And while to people who had no idea magic was real those words were interchangeable, for the supernatural set, calling a witch a štriga was the vilest insult imaginable. A štriga, Mom had said, was a witch who turned to the darkest magics, who enjoyed bringing pain and misery and death, who had nothing but hatred and selfishness in her heart.

And for people like Marijana, apparently every witch was just one bad day from becoming a štriga and there was simply no way to change their mind.

To Marijana’s mind, Mom had first tricked Dad into falling in love with her. Then she’d tricked him into getting her with child just so she could drive her hooks deeper into him. Maybe because she had some nefarious plans. Maybe because she was hiding some dark past and wanted to use him as a shield. But in the end, Jelena concluded and Mom had agreed, because Marijana was just a bigoted woman.

“No matter how hard you try, no matter what you do, and no matter who you are, some people will just not like you, and there’s nothing you can do about it,” Mom had said and Jelena took it to heart.

She’d asked Mom several times over the years. “Do you ever miss it? Do you sometimes want to go back to being a witch?”

But Mom’s answer was always the same: “I do, sometimes, but I chose peace and quiet, and then your Dad came into my life, we had you, and I don’t regret anything.”

“You really don’t mind if I do it?” came out of Jelena, took her by surprise but not really. It had been on her mind for a good long while now. “I can stay here. I’ll do it for you, Mom. I’ll give it all up and we can live here and have a simple life and—” Mom’s gentle hug stopped her from speaking when the woman stood up, walked over to her daughter, and embraced her.

“You don’t want that,” she heard her mother say softly, felt the hum of those words against her chest.

“No, I don’t,” Jelena breathed out. She would have done it, but she would have been miserable.

Mom pulled back, took Jelena’s face between her palms. “I want you to do what feels right for you. Your Dad wanted that and I want that. That’s what any parent wants for their child.”

Jelena’s eyes went blurry. Years ago, she found out that, from the moment she’d been conceived, chances had been significant she might one day show signs of being a natural-born witch or a bellringer, but also that her parents had spent years raising their—for the moment perfectly ordinary human—daughter without ever feeling like she was less than either of them. When she first expressed her desire to become a bellringer for the carnival, though, Mom had bet Dad that Jelena would one day feel the same call he’d answered. He’d chuckled and said he bets that their daughter will one day tell them she thinks she’s a witch.

“But it will also annoy that bitch immensely, and that’s a tiny bonus, I won’t lie.”

Jelena burst out laughing, wiping her tears as Mom made a face, faking being shocked at her own words.

“So,” Mom said. “Am I coming to pick you up after Let 3 or do you want to stay until the end?”

Jelena blinked. Oh, right. The music festival, that was this weekend.

“I—”

“You should go,” Mom said, smiling. “From what you told me, from what your Dad had told me, tomorrow is going to be… rough. Go have some fun with Tara.”

The Talk

About a year before she’d see the frostling on the car roof, she was no longer able to hold it in. The toll the past year of training had taken on her physically and mentally had started affecting her friendship with Tara. They had less and less time to hang out, what with the training itself and Jelena being dead tired after it, what with her having to avoid answering Tara’s questions about what she’d been doing yesterday or for the weekend, or why she couldn’t go to the cinema or concerts and so on and on—and Jelena wasn’t having it. She had realized that for the past several months she had been watching, in real time, as the deepest friendship she’s ever had was slowly falling apart and the thought of losing Tara that way hurt only marginally less than the thought of Mom dying one day.

She’d been working herself up for days, preparing in her mind for the inevitable fight she’d have with Mom and with Old Robert, but when she spoke to them—individually—they both had the same reaction. “Okay.” Both times Jelena could just stare and blink.

“But… it’s supposed to stay a secret. You said so.” Both of you. Repeatedly.

“Yes,” Old Robert said.

“So how…”

“You’re not supposed to tell the general public,” he continued, his raspy voice taking on a note of kindness. “But we all need someone in our life to share this with. Usually a spouse, often a parent, but, yes, good, close friends too.”

“Your dad would have told me even if I weren’t a witch,” Mom said. “And if he didn’t have me in his life, I think he would have told someone.”

“But you said…” Jelena sputtered.

“Oh.” Mom finally realized. “Oh, my love, I’m so sorry. I—I didn’t mean for you to think nobody ever in your entire life can know.” She looked mortified for a moment. “Oh, forgive me, please. I was just—you were so young, and this was going to be so hard, and I just—I didn’t want you to tell the wrong people and then have problems or create problems for Robert and the others —”

“Mom, it’s okay,” Jelena said, grabbing her mother by the hands she’d been waving about. “So it’s alright if I tell Tara?”

“Oh absolutely,” her mother said.

But Old Robert had a different reaction to the mention of Tara. “Will she keep it a secret?”

“Will you kill her if she doesn’t?”

He regarded her for a long moment as Jelena cursed herself for trying to be funny, although a part of her was genuinely interested in the answer.

“Nobody would probably believe her if she told them,” Old Robert said. “But some might hear about it who really shouldn’t and then… We’ve had problems before. People have died because somebody said something they shouldn’t have.” He spent a moment deep in thought. “I won’t stop you from telling her, but I want you to be sure about the choice you’re making.”

It was one of the few things in Jelena’s life of which she was absolutely certain.

It was only as she got Tara in a secluded, private space—accepting the other girl’s invitation to go for a walk in the woods on a nearby hill, the same woods where they used to play and look for tigers when they were kids—that Jelena suddenly felt an incredible dread rise inside her.

What if Tara thought she was nuts, certifiably insane?

What if Tara laughed in her face?

What if Tara thought she was a freak and didn’t want anything to do with Jelena ever again?

She ignored the fear as best as she could and when they sat on the rock in a little clearing on that hilltop where, for the past two years, they would go sit and talk and sometimes sneak a small bottle of bambus—she gulped hard and said: “I need to tell you something.”

And tell her she did. Everything. She lost track of time as she spoke, lost track of her own thoughts, was certain that, as words tumbled out of her mouth, they did so without any semblance of order, tripping one over the other until it was all just a huge, incomprehensible mess. But Tara was nodding and listening, eyes wide at certain moments, narrowed at others, mouth hanging open or speaking silent “no ways” and “reallys”.

Jelena finished with a “So…”, her entire body buzzing.

Tara was silent for a long, long time, just looking at Jelena. “It’s… weird.”

“Yeah.” Jelena said, getting up slowly. “Yeah, I know.”

“Where are you going?”

Jelena turned. She had already made it a few slow steps back down the path. “I—I thought you wouldn’t want to… I mean—” She didn’t actually know what she meant. Nothing made sense in her head ever since she dumped it all out in front of Tara, from opening the steel door all those years ago to her training session last week when she was finally allowed to spar using her father’s actual mace and not a training replica. It had felt like holding his hand again, and for a moment, she thought her heart might burst and she couldn’t see a damn thing. But she’d pulled herself together and started going through the motions, confidence growing with every swing.

Tara was on her feet now, glowering. “The fuck is wrong with you? I don’t care about any of that. I care only about you. You’re still my friend.”

Jelena had not realised how much she missed talking openly with Tara until that very moment. Nor did she realise how much she missed her hugs until a second later, when her friend closed the distance and held her tight, so tight.

“So, um,” Tara asked when they finally started walking slowly back to the village. “Can you, like, also turn into a wolf or something?”

Jelena sniffed. “No, unfortunately not. But I get a mace to beat spirits and monsters with.”

“Fucking A.”

***

Tara suddenly stopped just as they were about to enter Jelena’s front yard. Back then, the things she could see were still just hazy blurs and transparent blobs, but it still unnerved her for a moment to see something the size of a car and the color of copper perched atop her house. A second later it shot up into the sky and vanished.

“What’s wrong?”

“Nothing, I just… I don’t think I… maybe I should…”

Jelena’s voice was suddenly so hard she surprised herself. “If you have problems with my mom being a witch—”

“What? No! That’s cool as shit!” Tara snapped back, defending herself. Then she cast her eyes down. “It’s just… I mean… your mom’s always been cool, but now, with all this… what if she… I don’t know, what if she thinks I’m lame…?”

Jelena gaped. Then she laughed out loud, forcing herself to stop only because Tara looked so wounded. “Sorry, sorry, sorry,” she said, then grabbed her friend by the hand and started dragging her towards the house. “Come in and stop talking fucking nonsense.”

She opened the door and, still holding Tara by the hand, yelled out loud into the bowels of the house: “Mooom, Tara thinks it’s cool you’re a witch but she’s afraid you think she’s laaame.”

Tara was mortified, pulling on Jelena’s hand, but bellringer training trumped embarrassment-fueled strength and Tara wasn’t going anywhere.

Jelena’s mom appeared in the kitchen doorway with a half-eaten apple in her hand. “Oh, you’re back! Good, I’ve just checked the pizza dough, it’s rising, I think I finally got it right. Dinner should be ready in about forty-five minutes.” She smiled at Tara. “You’re staying for pizza, right?” Then she leaned a little forward, smiling still. “Sorry, honey, I didn’t catch that—”

“Yes, thank you,” Tara blurted out a little louder this time, still avoiding eye contact.

Jelena was a little… grumpy. Not that she minded Tara thinking her Mom was cool, because she was, but she kind of expected that her thing would be a bigger deal, yet Mom being a witch—a retired one—was apparently the only thing Tara really found impressive. So impressive she was actually having trouble talking to the woman whom she, up until yesterday, treated with almost as much casual familiarity as she did her own granny.

As they sat, eating pizza and chatting, first about school and then, when Tara had plucked up the courage, about magic—Mom offering only tidbits but even that had been enough to make Tara’s eyes almost pop out of her head—Jelena realized that whatever may happen when the trial comes, she’d feel happy that at least both people she cared for the most in her life knew who and what she truly was.

The Concert

“Riječke—čke—čke, najbolje su čke—čke—čke!” Jelena and Tara were screaming at the tops of their lungs, their voices melding with the concert crowd’s chanting as the band kept the chorus going and going, until the song finally finished and the set ended to a rabid cheering and clapping.

As the crowd slowly dispersed in various directions, mostly to get more drinks or find the portable toilets, Jelena and Tara moved closer to the edge of the Karolina pier, trying to get some of that cooler air above the still water of Rijeka’s port.

Things like ribbons or streamers flew through the air, dancing above the water, dipping high and low; some blue, others crimson, all slightly hypnotic to Jelena’s slightly tipsy mind.

As they walked, boys would occasionally cast glances their way, grown men too. The first was something Jelena ignored because tonight she just wanted to sing and dance and drink with Tara. The second… still made her feel icky and she didn’t think it ever would stop making her feel that way.

As adolescence and bellringer training started bringing changes to both her mind and body, boys suddenly started paying attention to her and Jelena didn’t mind, even though she wasn’t all that thrilled to be noticed. Prodded a little by both Tara and Mom, she went on some dates, but none went anywhere because none of the boys turned out to be really interesting once they sat down for coffee or ice cream.

The farthest she ever got was with a blue-eyed, dark haired boy who simply radiated confidence, who had teased her a little, in just the right way.

She let him kiss her when he leaned in. It was her first kiss, soft and tingly; a completely new experience.

Then he ruined it by trying to push his entire tongue in her mouth. She pulled back, asked him to slow down.

He was suddenly and inexplicably angry, asking why the hell was she teasing him if she wasn’t going to go for it.

She told him the date was over.

He grabbed her arm as she was turning.

Old Robert’s training kicked in without her even thinking about it and she twisted herself free with ease, slapping his hand hard.

He gave her a dirty look and stormed off.

The next day in school she overheard him talking to a few of his friends, laughing about how yes, he really did take the tall redhead for a date, she practically begged him to take her out for weeks, but no, he wasn’t going to do it again. Did he score? Well, you know. They all laughed, pushing him in the shoulder playfully, saying he’s full of shit. But no, they did kiss, though, and he could have gotten way more, but he didn’t want to. I mean, have you seen her during gym class? Way too many muscles for a girl, man, I don’t want anyone thinking I did it with a dude.

Tara found her in the toilet, crying. Gently but insistently she got the entire story out of her and the moment Jelena actually heard herself repeat out loud what that boy had said, she stopped being sad and angry and self-conscious. The hell was she doing? Why was she crying? Mom would never cry about something a dumbass like that either said or did. Dad would never do or say anything like that idiot. Who the hell was he that Jelena should cry and get all worked up about him?

Then she had to use all her strength to actually physically hold Tara back and stop her from stomping out of the toilet to track the boy down and do something that would probably get her disciplined if not outright expelled.

***

“I need to pee,” Jelena told Tara. She’d needed to pee for a while now, but there was no chance she’d leave the front row at a Let 3 concert to go pee. Physically it would be doable, but she would not miss out on the sheer delight of the experience even for gold.

But now her bladder was threatening to burst, so she told Tara to go get a drink on her own and she’d join her at the beer stand.

She spent a few tense moments looking for a vacant portable toilet. Some were facing the pier, others the port, and to a tipsy and endorphin- and adrenaline-riddled Jelena, the search for a door that could not only be open but was actually a door and not the back side of a portable toilet seemed to last for an eternity.

Finally, though, she found what she was looking for.

A few minutes later, with a pep in her step, she came out, turned, and saw someone standing too close. A little shorter than her, slim but muscled. Doc Martens on his feet. A shaved head. A nasty look in his eyes.

There was no one nearby. How could there not be anyone nearby? But the row of portable toilets formed a wall between Jelena and the other festival goers. It was just her, the boy, and the calm sea; even though there were literally hundreds of people just a few metres from them and the entire port was well-lit by street lamps and stage lights.

“Nice shirt,” he said, staring at her hard. Jelena cast a glance down, afraid that it had torn during all that jumping in the front rows, that her breasts were exposed, but no, the shirt was like when Mom had gifted it to her years ago. Sure, the black was faded from wearing and repeated washing, but the logo was still clear and—

The logo. Rage Against The Machine. Absolutely not the kind of lyrics and political stance a skinhead would approve of.

She didn’t have her mace, but she had been trained to fight without it. Yes, but not fight… a human. A drunk boy about her age, eyes clearly eager for violence and other people’s pain. And he probably carried a knife. And Jelena was tipsy, just a little wobbly on her feet.

“Please, just let me pass.”

He leaned towards her, baring his teeth as he produced a switchblade almost from thin air. “Since you like Commie cunts,” he said, leering at her chest now, “how about I carve a nice red star on your forehead?”

The world seemed to stop—but only for a heartbeat.

“Hey, handsome?”

He turned his head just in time for the heavy plastic beer bottle to slam into his face. He yelped, dropping to the ground as Tara’s Doc Marten’s slammed repeatedly into his stomach and side.

“Steel—cap—you fucking—piece—of runny—stinking—shit!” Tara growled at him as he begged for her to stop.

Jelena grabbed Tara by the arm, pulled her away as the skinhead whimpered in a foetal position.

“Come on,” Jelena said as she dragged Tara back toward the festival crowd.

“Should have let me—”

“You’re fucking crazy!” Jelena snapped, stopping.

“Excuse me?!”

“What—what if he calls the police?”

Tara snorted. “Yeah, I’d like to see that, a skinhead calling the cops because somebody beat him.”

“What if he has friends?!”

“Sure. He’ll tell them a girl jumped him.”

As they walked briskly, Jelena’s thoughts roiled. What if she freezes tomorrow like she did just now? She’d sparred with Old Robert and other bellringers, only she won’t be fighting people tomorrow, but creatures she’d only seen in drawings, photos, and on video footage. Yet tonight she froze—

No. I didn’t freeze. I just didn’t want to fight him. I just didn’t want to risk getting hurt.

Yes, that was it. It had to be that.

Half an hour later, Mom was waiting for them in her car, at the edge of the pier.

As they sat down in the car’s back seat, Jelena’s mother turned to them, smiled and asked if they’d like a snack. Before either of them could answer, she handed them a plastic box full of fresh baked cheese and ham pastries and the smell was enough to make both girls hungry even if they hadn’t been before.

***

There had always been a place for Tara at their table, ever since the two of them became friends back in kindergarten. Eating together was something Jelena never paid any attention to, it was as normal as them playing in the old goathouse, running in the meadow, or sitting at the same school bench.

It was when they were nine that Mom asked Jelena if everything was okay with Tara, if she maybe mentioned to Jelena anything about her parents, about how things were at home.

Jelena had no idea what Mom had been talking about. Sure, Tara’s parents would sometimes shout so loud Jelena could hear them from her room, even though their house was quite far away, on the other side of the meadow. And yes, Tara didn’t really like them playing at her house, but Jelena always guessed it was because Tara’s house only had a concrete garage and no goathouse or sheds to play in.

This made Jelena start wondering why Mom would ask such a thing, which made her pay attention, which made her notice things. Things like Tara’s clothes often looking rumpled, like they’d been washed but not ironed; sometimes with holes in them that would take days to get mended. Things like Tara forgetting to bring textbooks or notebooks to school or bringing the wrong ones. She started catching Tara looking at her school lunch after practically inhaling her own, then turning her head away quickly so as not to get caught staring at Jelena’s.

She wanted to ask Tara about it all but was either afraid or nervous, or simply, as a child, had no experience with such conversations.

But she could always talk to Mom and Dad about anything. So she told them and they exchanged long looks, sad and worried. They told her that it’s good she spoke to them, that everything would be fine with Tara.

The next day Mom made two sandwiches for Jelena before she left for school. Jelena said it was okay, the lunch the school made for them was always enough, but Mom gave her the sandwiches anyway. It was only as they were eating at the big break, with Tara devouring the hot dog and mug of cocoa that Jelena realized why Mom had given her the sandwiches. As casually as a child of nine could, she took out the plastic bag and offered it to Tara, saying she wasn’t really hungry, but maybe Tara would like some?

Jelena’s mother kept making sandwiches and Jelena started inviting Tara over for lunch and dinner every opportunity she had. Mom and Dad didn’t mind and went like that until about six months later, when Tara’s father left the house in the middle of the night and her mother moved to her sister’s apartment in Rijeka while Tara’s maternal grandmother Kata moved into the house across the meadow, “to look after Tara just for a week or two”. This all happened on the same day, and for four days straight Jelena didn’t see Tara. When she asked her parents, Mom told her that everything was fine, Tara just probably needed some time alone, and Dad did his best to explain to Jelena that sometimes parents just stop feeling like they’re right for each other and then it’s best that they go their separate ways. Then he had to assure a terrified Jelena that wasn’t going to happen to him and Mom and that they’d never leave each other or her.

The next day, as Jelena wandered the backyard, she discovered Tara on the top floor of the goathouse, where they’d long ago set up their “spaceship”: computers made out of cardboard boxes, a large square mirror they had stealthily removed from the wooden shed, now repurposed as a “holoscreen”, tubes and wires strewn about all over the place. Tara was in the corner, sitting next to an old, large milk bucket with several holes in its side—their “warp core”—and crying her eyes out.

Jelena didn’t know what to say. She felt so many things but had no words to express it. Fortunately, it took her only a heartbeat to realise she didn’t need to say anything. For Tara, it was enough that her friend sit down next to her, hug her, and stay like that for a long, long time.

***

As the car trundled along up the road to Grobnik, Jelena felt Tara’s head bump against her shoulder. Her friend—her saviour, she thought with a smile because the danger that boy had presented had faded away and her mind could focus on what Tara had done instead of what he might have done—was asleep. Jelena hoped she’d be able to do the same once she got home. The festival had been that final separator between her entire life so far and… tomorrow, and now there were not years, months or days, but hours. Only hours.

The Clearing

“Girls can’t be bellringers.” It’s what they told a six-year old Jelena and crushed her dreams in an instant. A boy in kindergarten had said it first and then, when Jelena asked Mrs. Vera, the teacher, hoping she’d give Jelena proof that the boy had no idea what he was talking about, the old woman smiled at her and said, “Yes, it’s true. That’s just for the boys.”

She wanted to be a bellringer so bad, that first time she’d seen them. Dozens of them, to her as tall and big as giants. The skull helmets, scary to a child but in an exciting way, the fleece over the plaid shirts, the clubs, but most of all, the bells. Cow bells, huge, tied around their waists by chains or leather straps, clanging as the bellringers made their way slowly down the road through their village.

“They’re chasing away winter so that spring can come back,” Mom had explained when Jelena had asked what was happening. She had stood in the front yard, looking at the procession with eyes as wide open as possible, holding Mom and Dad’s hands tightly. Entranced by the sight, but most of all by the noise, the chaotic clangor that filled the world and her head.

She’d see them again weeks later, because Rijeka had a carnival and the grand procession would always be closed by the bellringers: after a long day of carnival groups and floats passing the length of the Korzo promenade, after the sun had already long set, the bells would come. Yes, to Jelena it was even scarier because now it was dark and they seemed even more menacing, even more monstrous, but she wouldn’t have asked Mom and Dad to take her away even if Korzo had been on fire.

The day after the carnival was the day she’d proclaimed loudly to her kindergarten group that she would grow up to become a bellringer.

When she came home afterward, despondent and finally admitted to her parents why, they’d exchanged a glance, smiling, and her Dad barely suppressed a chuckle. “Honey,” he’d said. “If you want, I’ll make you a bellringer costume for next year’s carnival.”

He hadn’t because next year Tara and Jelena’s elementary school class went to the children’s carnival as the 101 Dalmatians, but while Jelena had forgotten her firm desire to be a bellringer, she did feel that strange buzz and elation at seeing the procession.

***

Now, as she stepped out of the car, the spring sun shining bright from a cloudless, blue sky, she wondered what that six year old Jelena would have thought of her. She would probably be struck speechless. And then focused on Lola, because bellringers were cool, but dogs were the best.

Tara had asked if she could come and bring Lola, and was told yes by Old Robert, as long as she obeyed the rules strictly.

They were all out of the car, Jelena and Mom and Tara and Lola, standing under the shade of a large oak tree. There were several other cars parked there, empty. The woods were sparse here on these foothills at the edge of the Grobnik field.

There were people in the distance, at the edge of a clearing: still dressed in everyday clothes but each had their own large and heavy burlap sack nearby, currently making up a small pile.

“We’ll be right behind,” Mom told Jelena as she took a breath, swallowed hard.

“Shit,” Jelena said, patting her jeans’ pockets. A breeze had ruffled her shoulder length light red hair and made her realize she’d forgotten something.

She looked at Mom. “I—I don’t have a scrunchie or anything—” She didn’t want to do the trial with her hair flapping about her face, distracting her in the worst possible moment.

“Here.” Tara started biting her wrist—no, untying one of her several leather cord bracelets there. A moment later she put it in Jelena’s palm; just a thin piece of leather with some metal tchotchkes hanging off it.

Tara stepped closer, holding Lola’s leash tight because the dog equated woods with running free and was eager to start doing just that. Tara breathed out hard, looking as tense as Jelena felt. “You come back out alive, you hear me?” she said in a shaky voice. “Or I swear I’ll learn magic, raise you from the dead and kick your ass.”

Jelena hugged her and Tara hugged back, eyes wet with tears, Lola trying to push between them, join the fun.

And then Jelena turned, swallowed hard once again, and started walking.

With each step she was closer to the bellringers waiting at the edge of the clearing, and the more she felt the world fall away from her.

They all turned to look at her now, scattered in groups.

Jelena saw Brane give a friendly wave; Valter open the Book of the Bells; Old Robert stand upright, his bearing as if welcoming visiting royalty. She saw Sanja and Ivana nod at her as she approached, Alen rub his hands and grin encouragingly, and Mirna give her a tiny smile. And there were Marijana, Jakov, and Tone, their faces impassive, their eyes cold.

***

Things would happen occasionally, after Jelena’s parents married. Wooden boards would appear overnight in their backyard, painted with symbols that looked like random lines and shapes, unless you knew magic was real. Then they’d be slurs and threats. And once, there was a goat’s head—black fur, broken horns, and the tongue pierced with long, rusty nails—left in the old wooden shed.

“An entire goat house, and they put it there instead.” her Mom had chuckled as she told the story to Jelena. A shocked Jelena, and then an angry Jelena.

“Who did it, did you ever find out?” she had demanded.

Mom had waved it off. “We could never find concrete evidence. I mean, I could have but…” She sighed. “I’d have to use magic to track them down and then they’d use that against me.”

The boards and the severed animal head had been warnings. “Leave.” “Stay away from this place.” “We don’t want your kind here.”

“Servant of the Devil, this is what’s going to happen to you,” Mom said. “That’s what the goat’s head was supposed to say. I think. I mean, if the Devil exists, at least the Devil people who leave messages like that believe he does, the last person he’d want for a servant is an ex-witch like me.”

But while Mom and Dad had no evidence, they did have suspicions. Marijana, Jakov, and Tone. The messages had stopped appearing after a year or two, and by the time Jelena was born, any unpleasantness was limited to mean looks and murmurs directed at Mom, and only when Dad wasn’t nearby.

***

She stood in front of them now, once again: the ten bellringers—true bellringers. The ones Jelena had been smitten by as a child were what had managed to, over the centuries, seep into the folklore of people who knew nothing about real magic and the real supernatural. The bellringers from Grobnik and other places were folk traditions based on glimpses and overheard whispers about the real thing, often melded with other folklore and traditions.

She’d asked Dad, Old Robert, and a few of the other ones if it ever bothered them; in the end, keeping the existence of true bellringers a secret was paramount, and yet, there were their very murky reflections on television and the Internet, in museums and during carnivals.

“It’s good, actually,” Dad had said. “That way, if someone potentially witnesses me or someone else in our gear, they think we’re just going to the carnival or practising for a procession.”

Valter cleared his throat as the men and women stepped closer, forming a semicircle, eyes locked on Jelena. She was doing her best to keep her back straight, return their gaze, and not show just how tense she was. Her stomach was a steel knot. But she would not back down, no matter how much three particular pairs of eyes wanted her to.

“We are not alone,” Valter spoke up, his blonde hair almost glowing in the sunlight. “Since the first of us was called to our duty, we bellringers have known this. The world is bigger and stranger than any can imagine, stranger than anyone will ever truly know. There are witches and vampires and werewolves; štrigas and dragons and trolls; ghosts and chimaeras and nymphs, and so much more. There are woods you can wander for decades and never find your way out, lakes where you can breathe water like air, and carved rocks that will take you from one world to another.”

His voice was clear, the silence solemn. Even the breeze that rustled the oak leaves seemed to stop blowing out of respect for what was at hand.

“There are many dangers, many monsters. Many predators who stalk the unsuspecting, the unaware. And there are those who protect; those who fight the monsters. A bellringer knows them: witches, sorcerers, krsniks, and more.”

Pride and steel crept into his voice now. “But what we do, only we can do. The world we see, only we can see unaided. The monsters we face, only we can wield the true weapons to defeat them. The spirits and dangers we keep at bay, only we know the true ways. We know this because we feel it in our bones, in our very core. We know it from the moment we are called to our duty.”

He glanced at the faces to the left and right of him, then looked back at Jelena. The words had reached something deep inside her and she couldn’t stop imagining Dad listening to these words, standing at the edge of this clearing, decades ago. She’d have given anything for him to be here today, that there were eleven instead of ten pairs of eyes locked with hers.

“Others could stand up to them, fight them, defeat them, yes,” Valter continued. “But we are best equipped to take on those battles. Seasons would change without us; they had been changing for countless aeons before the first bellringer was born, but the change would be more violent and would bring about dangers that we stand as a wall against.”

There was such passion in his voice and on his slightly pockmarked face Jelena couldn’t not feel herself being swept up in it.

“The world of man is like a beacon to the spirits, the wraiths, and the countless other dangers that lurk in the dark.” He puffed out his chest a little. “And so we don our helmets and wield our weapons, and the ringing of our bells ushers in the change of seasons and keeps the darkness at bay, all for the world of man; the world we were born in, the world we trace our roots to, the world we keep one foot firmly in.”

Silence reigned as Jelena recalled a moment from her training, Valter’s words bringing back the memory as if replaying a movie in her mind.

***

It was in the low barn behind Old Robert’s house, the one that had decades ago been converted into the bellringers’ training hall, unknown to any of his neighbours. Sweaty and aching from the merciless sparring sessions with Sanja and Alen, Jelena listened to Old Robert talking, as her sparring partners were getting dressed some distance away, giving them privacy.

“You won’t be hailed a hero. Heroes get songs and tales spun about them; they get glory.” Old Robert waved it off like swatting a fly. “You won’t get those things. You don’t need them.”

He grew solemn, regarding Jelena with the eyes of a man who’d see maybe too much, the weight of decades a heavy, melancholy presence in that gaze. “You will get pain and trepidation. Broken bones, blood, and dark dreams.”

He turned to the long wall of the barn to the right of them; boards carved with reliefs of skull-helmets and names. Dozens and dozens of bellringers long gone.

He placed a firm hand on Jelena’s shoulder. “But you will also have them. The people who wear these helmets will be your brothers and sisters, bound by battle if not by blood. You will be one of us and that is all you’ll ever need.”

Then, a little softer, he added: “Us and the people closest to you. When I was young, I thought I’d crave recognition of strangers for what the bellringers do. The day after my trial, I knew, with absolute certainty, that I don’t need anybody to thank me. It would be nice, but all I really needed was the look in my Višnja’s eyes every time I’d come back to her.” He sounded wistful and Jelena kept her eyes on the rows of carvings, not wanting Old Robert to feel embarrassed if she noticed the tears in his eyes, the ones she could absolutely hear in his voice.

***

And they were here now, faces and eyes focused on her. The final step was here and she had to make it because…

Yes, because all that she had been doing for the past years would have been a waste of her and others’ time. Yes, because she inherited these powers from her Dad and they’d go to waste if she failed or gave up. Yes, because she could feel the call to protect and defend, a persistent presence in the depths of her very being.

But none of that was the reason to make this final step.

She wanted it, and that was it. It was simple and clear; it felt right to do it and it was all that mattered.

“Jelena, daughter of Borna,” Old Robert spoke up in a firm voice. “You come to face the trial of the bells. Once the trial begins, the only way out alive is through. I ask you, here and now, are you willing to take on the trial?”

“I am.” She had thought she might hesitate, that her throat might become drier than sand, that she’d falter for just a moment. But it came out of her as easy as a breath.

Old Robert gave a solemn nod and the bellringers parted to the left and right.

And Jelena’s breath caught.

At the far end of the clearing, where moments ago there was just the occasional tree, tall grass, and small rock, a cave appeared.

The opening was wide and low, irregular; a patch of inky black bordered by gray rock that slowly went from solid to see-through to simply not there as her eye followed it outward.

The things only the bellringers could see now reacted to it: leaning from the branches, rising from the grass, standing still where they’d been passing across the clearing. They watched it, motionless, seemingly entranced.

Old Robert set a small cloth sack in front of her and Jelena started preparing for the trial. She took her long-sleeved shirt off and removed the tunic from the sack, pulled it over her head. The fabric was thick and warm against her skin. She had to roll up the sleeves twice for them to reach above her wrists; it hung loose almost to her knees.

The tunic was white, almost blindingly so under the noon sun.

Next she took off her trainers and her jeans, revealing the dark gym leggings under them. Once inside, she knew she’d need agility and speed and she loved wearing jeans, but they’d only restrict her.

She took off her socks, felt the warm grass and earth under her feet, pleasant and just a little tickling for a second or two.